Our latest paper is now out in Science Advances and features on the cover

Our discovery of an epidermal membrane-associated periodic scaffold that protects axons from damage has been published in Science Advances and features of the cover of the issue.

Lateral view of nematode C. elegans larvae, with endogenously labelled b-spectrin/UNC-70 (pictured in black). The cover of the January 9 issue of Science Advances. Credit: Igor Bonacossa-Pereira.

Neurons communicate with one another via long cable-like structures called axons. These projections can reach lengths of up to 1 m in humans and 30 m in some species of whale. These very long and extremely thin projections are subjected to force as we grow, as well as when we move. These range from tiny forces that allow the detection of touch and pressure, through to much larger forces imparted by body movements such as limb flexion and extension, where peripheral nerves in mammals can be stretched up to 30% of their length. While an intact nervous system is critical for normal function of the nervous system, we still do not understand the fundamental mechanisms that enable axons to tolerate constant mechanical strain.

A major structure presumed to impart axons with an intrinsic ability to withstand strain is the axonal membrane-associated periodic scaffold (MPS). This is made of cytoskeletal scaffolding proteins, the internal framework of a cell, that form a lattice-like structure inside axons with a very precise spacing of ~200 nm. This nanoscopic series of trusses and beams inside the axon is understood to function like a spring to buffer strain and maintain tension and elasticity within the axon.

However, on its own it is not sufficient to allow sensory axons to withstand the strain of body movement. If we specifically disrupt the axonal MPS inside neurons that detect touch in our favourite roundworm, C. elegans, these axons remain intact. In worms, as well as in humans and other species, the sensory axons that are necessary to detect touch, temperature and pain are embedded in the skin. When we looked in this tissue, we discovered a similar nanoscale structure, which we called the epidermal MPS, that surrounded sensory axons and outlined a striking imprint of the underlying nervous system. Importantly, this epidermal MPS is essential for the integrity of sensory axons. Without it, these axons spontaneously break and undergo axonal degeneration. We propose that this structure is important to maintain cell-cell attachment between sensory axons and the surrounding epidermis to buffer the effect of physical force during movement.

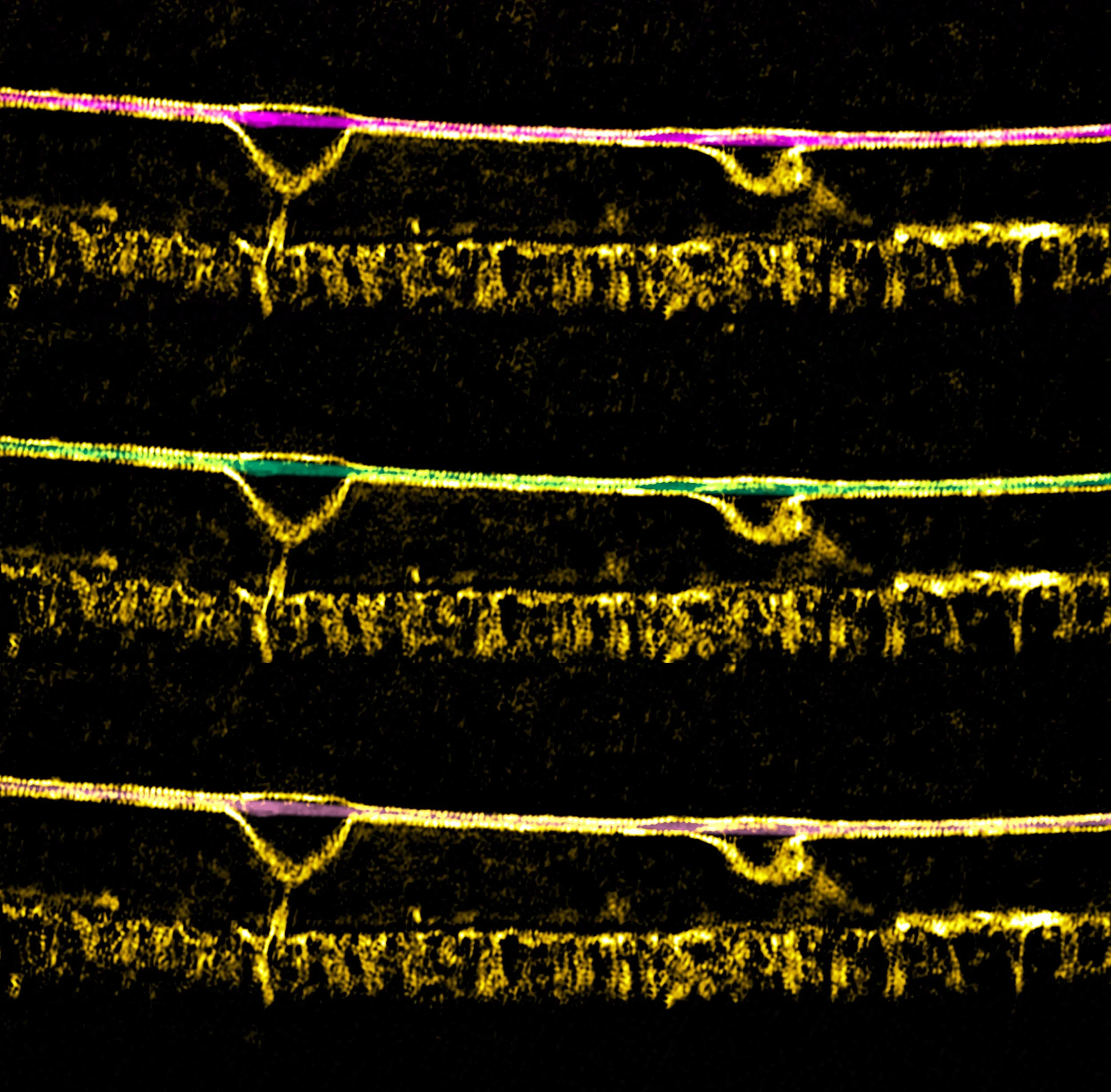

Structured Illumination Microscopy of the axon of a mechanosensory neuron (pictured in triplicate in violet, green and magenta) of the nematode C. elegans showing an epidermal membrane associated periodic scaffold (pictured in gold) surrounding the axon. Credit: Sean Coakley and Igor Bonacossa-Pereira.

Our findings provide a major conceptual advance and suggest that complex interactions between tissues may buffer forces experienced by the axon during body movement. We are working hard to further characterise this unique cellular structure and understand more about how neurons are protected from force at a molecular level. This is a major focus of our lab moving forward and we are always on the lookout for talented and curious scientists to join us.